But this place has a history attached, inescapably, dragging on its heel. During World War II, the American government issued an executive order that condemned Japanese Americans to internment in camps for "national security." The government felt that these citizens and residents, given their heritage, posed a danger, and so they isolated them. Rounded them up, in places like Puyallup, Washington (the site is now the Puyallup Fair), put them on trains and loaded them into several camp sites across the US. Once in the camps, these unfortunate citizens and legal residents of America worked making camo garments for American troops overseas, drawing vegetables and sustenance from the desert's soil, going to church and playing baseball. The government, wanting to justify their internment of US citizens, sent Ansel Adams to photograph the camp residents and show how happily they sacrificed their freedom, their land, their homes, their families, how they understood this was necessary, how they weren't angry about it. This was Adams' most controversial job. His photographs portray a sunny, industrious group of Japanese; these photos contrast with those of Dorothea Lange, famous for her capturing of the Great Depression, and Toyo Miyatake, a resident and photographer. Lange and Miyatake caught fragments of the camp's toll on its residents, their confinement, and their difficulty living in one of the most extreme sites on earth, with its withering summers a testament to nearby Death Valley and frigid icy winters, their wafer-thin holding blocks affording the camp residents poor protection from the elements.

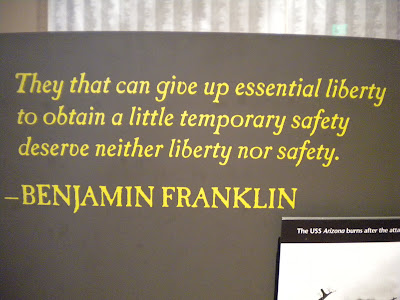

Much of the camp was destroyed, dismantled by the government after WWII, an embarrassing show of America's paranoia and inflicting un-Constitutional action on her own citizens. Today, the site is run by the National Park Service, with a self-drive auto tour and an Interpretive Center. We arrived at 8am, and enjoyed the site to ourselves until around 9a. It was so beautiful, so peaceful, so sad. The zen garden created by the camp's residents has been recreated, but other than that and the cemetery, solitary markers (Block 25, Church, Baseball Field) are the only pieces left standing. At the cemetery, a white stupa with black Japanese script on it stands alone in a square, fenced in with wooden slats decorated with strings of origami paper cranes, startlingly colorful against the backdrop of the desert and her muted colors. Visitors have left coins, necklaces, mementos, small Buddhas on the steps of the stupa, spontaneous pieces of their hearts left behind as a sign of their presence, their witness. Only six graves remain at the site (families have petitioned for the return of all other remains originally there), and seeing these mementos brought tears to my eyes. I want to believe that this place is not forgotten, that these six lives still are heard and that their lives, dishonored by ending captivity, are redeemed as rehonored by every person who comes here and walks away touched, vowing that America cannot take these liberties from her citizens again, that this compromises our principles and our founding and who we claim to be in the world. The Interpretive Center provides much of the backdrop and documentation of the stories of these Americans: their lives, their names, the stores and farms they owned before they came to Manzanar. It is my fervent (there is no other word) wish that this place continue to exist as an admission of America's mistakes and a call to who we can be: a place of liberty and justice for all.

No comments:

Post a Comment